|

The Story of Adam Fridberg

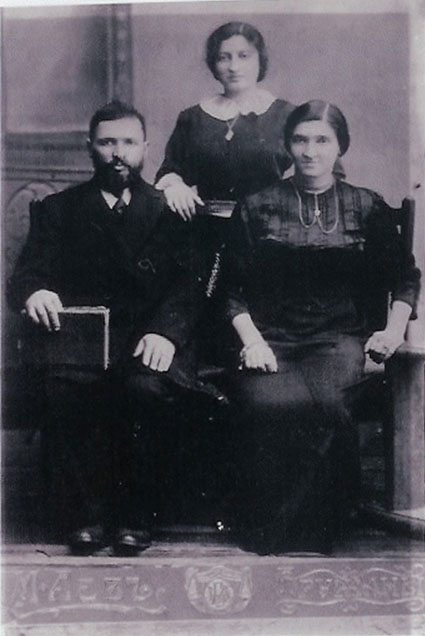

I was born in 1925, in the Polish township of Pruzany, to parents who had moved there at the turn of the century. My parents - Tzira and Moshe Frydberg - came from nearby villages, whose population was a mixture of Jews and Gentiles. The latter would harass their Jewish neighbors with acts of robbery and the occasional murder. With the passage of time, most of the rural Jews flocked to the towns and cities, where they were safer and enjoyed a better livelihood. Accordingly, Pruzany’s Jewish community grew steadily until it numbered 6,000 out of the township’s overall population of 8,000. Of the other townsfolk, most were Byelorussions; a minority were Poles despatched by the government to staff administrative posts. Pruzany was founded in the fifteenth century by Gentile Poles. Various legends were present as to the origin of the name: most probably it was derived from the river Pruzanka, whose course traverses the township on its way to the river Muchavetz. Following closely on the heels of Pruzany’s Gentile founders, Jews moved into the town, where a synagogue is known to have existed in 1463.

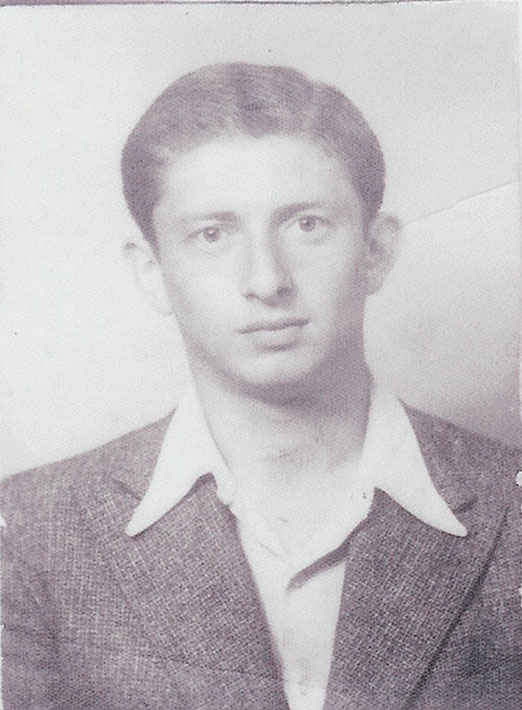

Pruzany lay near Brisk (known to Jews as Brisk DeLita, it was the same Brest-Litovsk where, on March 3, 1918, towards the end of World War I, Germany and Russia concluded a separate peace). Other neighboring towns were Kobrin and Pinsk, likewise populated by large Jewish communities. My father was not a Zionist, but my mother, who was active with charitable groups and other community associations, was drawn to Zionism. However, there was never talk at home of fulfilling the Zionist ideal by alia to Eretz Yisrael. The language spoken at home was Yiddish, but Mother had my brother and myself registered at the Hebrew school. My brother and I initially attended Yavneh, the Hebrew elementary school, going on to the Tarbut ‘gymnasia’. Both schools were walking distance from our home. On September 1, 1939, World War II broke out. The German army, with an estimated 1.7 million troops, mechanized and mobilized, with an abundance of tanks and aerial superiority, invaded Poland. Advancing with swift ease, the Germans overwhelmed the Polish army, which was inferior in numbers and equipment. Many of the people in Pruzany fled eastwards. But the east provided its own menace. On September 17, 1939, the Soviet Union, having concluded a non-aggression pact with Germany on August 23, invaded eastern Poland - in part due to the Kremlin’s concern over the deployment of German forces along its western borders. The Red Army met up with German troops at Brest-Litovsk on September 19. That same day, a Soviet advance unit reached our town. The victors promptly set about dividing Poland between them. The German and Soviet foreign ministers, von Ribbentrop and Molotov, convened on September 28 to amend the prewar Moscow accord. During the night between June 21 and 22, the Russians held a practice alert in Pruzany, with schoolchildren taking part alongside the grownups. It was a mild spring night, and many of the youngsters enjoyed the nocturnal drill, as though it were a night game in the youth movement. While we were dispersed in the fields outside the town, planes appeared overhead to launch a bombing raid. “It’s part of the alert,” we were reassured by the Soviet soldiers who supervised the exercise, “They want to make it appear realistic.” We returned home in the early morning to hear on the radio that war had broken out between Germany and the Soviet Union. It was later claimed that German spies in the region had instigated the exercise alert as a smoke screen for the invasion. On June 24, 1941, while we were still stunned by the news, German tanks reached Pruzany, which lay less than 20 miles from the border. The Russians in the area fled for their lives, heading for Soviet territory. Some of the Jews joined them in their eastward stampede. When the German units entered Pruzany, the Christians poured into the streets to welcome them, but the Jews withdrew into their homes. We had heard rumors about the persecution faced by Jews in the German-occupied parts of Poland; even before the war, numerous Jews from Reich territory had been deported to Poland. When the Germans reached Pruzany, we preferred to keep out of their way. Much of what I did not know at the time became clear to me after the war. The Polish province of Lomza, and the portion of Grodno bounded by East Prussia to the north and the Generalgouvernement to the south - an area the Germans dubbed Generalkommissariat Bialystok for the city of that name - were attached to East Prussia and therefore partially integrated into the Reich. Under this division, our situation was initially better than that of the regions administratively attached to Poland. The advancing German army was followed by the Einsatzgruppen, units which specialized in “handling” Jews. Their arrival was accompanied by anti-Jewish decrees; Jewish homes were attacked, Jews were subjected to robbery and abuse. Abetted by anti-Semitic elements and collaborators from among the local population, the Germans herded the Jews together, massacring them by the thousands. Initially, they burnt the corpses in great pits; later, they developed more efficient techniques. The Einsatzgruppen were backed up by the German civilian administration, which established ghettoes in the larger Jewish towns. The Judenrat was required to comply with the demands and orders issued virtually daily by the German military commander. Anxious to alleviate conditions in the ghetto and ease contacts with the authorities, the council shouldered a range of organizational and economic tasks. Having been confined to the ghetto, we knew nothing of the developments at the various theaters of the battlefront, where the Germans were beginning to suffer setbacks; but we did sense their viciousness growing with each passing day. Refusing to await liberation, some - young people in particular - resolved to flee the ghetto and try their luck in the nearby forests. Those who fled hoped to join the partisan bands active in the nearby forests. A few did indeed enlist with the partisans, but others were rudely rejected. On January 28, 1943, the Gestapo chief entered the offices of the Judenrat to notify its members that the residents of certain streets - 2500 persons in all - were to prepare for departure within a few hours. “They are being sent to work in Silesia,” announced the Gestapo official. “They are to take all family members, including the elderly, babies and invalids. They are authorized to carry small packages, and are advised to take their money and jewelry, and all valuables.” Thus commenced the evacuation of the Pruzany ghetto. It took four days to complete. The ghetto was evacuated in four transports. Of the 9,161 Jews hitherto resident in the Pruzany ghetto, 1,775 men and women ultimately reached the Auschwitz camp. Upon arrival, we were left confined to the train for hours while the station was cleared of previous transports. In the afternoon, the freight car doors were flung open. “Out of the cars!” In harsh tones, the German command boomed from the loudspeakers. “Packages are to be left in the cars!” As a rule, the selection went through with no questions asked. Only in rare cases did the officer pose two queries: “How old are you?” and “What is your profession?” It is evident, in hindsight, that anyone who admitted to a clerical calling was consigned to the gas chambers. Those claiming to be builders or electricians, etc. were retained in the camp. When asked about my age during the selection, I gave my year of birth as 1924 - making me one year older than I was at the time. I believed it would be helpful to claim that I was no longer a child. Of our transport, the men received the numbers 99211 to 99504, and the women - 33928 to 34023. I was given the number 99288. My brother got the number 99287. Our billet (Block) was a former stables that stood approximately 120 feet long, 30 feet across and eight feet high (specifications I discovered subsequently in the Auschwitz archives gave the average block a floor area of 390 square meters, and a volume of 1,200 cubic meters) with 500 prisoners crammed into each block.

My brother did not hold out in the conditions of the camp. He did not turn into a Mussulman, but he became enfeebled and disheartened. “I can’t stand it any longer,” he told me repeatedly, in broken, stifled tones. My efforts to encourage him were only briefly effective, for conditions in the camp were against me. “I don’t feel well,” he told me in dull tones, “I’m going to the sick parade.” I tried in vain to dissuade him. “Don’t go,” I said, “hold on, it’ll pass.” Though new to the camp, I already understood that the Germans could not care less if inmates died. Every evening, long lines of prisoners waited outside the doors of the camp hospital, in hopes of receiving medical attention or possibly hospitalization, which held the potential for better food, or a bed more comfortable than their bunks in the block. In view of the grave shortage of beds, most hospitalization requests were turned down; those prisoners admitted to the hospital after attending sick parades rarely returned to the camp. All the same, my brother insisted. He reported for sick parade and was sent to the hospital. I learned subsequently, by reference to his serial number, that he was hospitalized for three days until March 18, 1943, when he was dispatched to the gas chambers. During 1943, there were six gas chambers in simultaneous operation at Auschwitz; five crematoria burned thousands of corpses a day. The “death factory” operated at an even faster rate in 1944. With no prospects of survival in the camp, escape offered the sole hope of salvation. Most of the escapees from Auschwitz were Poles, who enjoyed relatively better conditions. Occupying 80% of the key posts in the prisoners’ internal administration and important jobs in the hospital and workshops, they were able to initiate underground resistance, to establish links with the outside world and prepare hideouts for prisoners intending to escape. Only from 1943 onwards did a few Jewish inmates contrive to get posts in the camp hierarchy, whereby they too could plan escapes. However, a mere 76 Jews managed a getaway from Auschwitz-Birkenau. They got no help from the Polish resistance movement and, in the absence of outside aid, most were recaptured. A mere dozen Jews are known to have made a successful escape. As a rule, any escape attempt was difficult and risky. But it was relatively easier to make a getaway from Birkenau, where the numerical ratio of SS guards to prisoners was 1:64, as opposed to 1:16 in the main Auschwitz camp. The escape route was as follows: the camp was divided into two sections, internal and external. The former was the residential section containing the huts (stables). It was surrounded by an electrical fence that was floodlit at night. At 50 meter intervals along the fence, tall sentinel towers served the smaller inner guard cordon, which was manned by sentries who opened fire on any prisoner that approached the fence. The inner watch was removed during the daytime, to be replaced by the wider external cordon (‘Grosse Postenkette’) which encircled the larger section. Comprising dozens of square kilometers including the SS quarters, this “protected area” was where the prisoners’ labor squads were employed when they were let out of the smaller fenced area. SS men manned the tall wooden sentinel towers, firing without warning at anyone who ventured in within 10 meters of the outer guard line. Every morning, when the labor squads had left for work, the watch was transferred from the residential section to the work section. Every evening, on the prisoners’ return to the camp, a count was held. If all were present, the Germans would remove he larger guard cordon to install the smaller cordon around the inner residential camp. If the evening count found one or more prisoners missing, the alert sirens were sounded at once. The outer cordon guards remained at their posts for an additional 72 hours while searches were carried out. Aided by trained tracker dogs, special units conducted meticulous searches in the work areas. After getting away from the external area, a new battle for survival lay ahead for the escapee, particularly if he was a Jew. An area extending 40 square kilometers around Auschwitz, between the Vistula and Sola rivers had been cleared of most of its Polish inhabitants, who were supplanted by German settlers. Whenever an Auschwitz prisoner escaped, the camp commandant immediately alerted the regional authorities to launch a vigorous search, filtering through public transport and the homes of the area’s former olish population. The escape technique accordingly called for a hideout to be prepared ahead of time in some civilian population center far from the camp; but it was vital to first locate a hiding place in the outer area for the mandatory three-day wait until a getaway became feasible with the guards’ departure on the fourth day. The location of the hiding place was transmitted in strictest confidence from one group to the next: anyone planning a breakaway would pass down the secret to the next potential escapee. It goes without saying that, if the escape attempt resulted in the Germans discovering the hiding place, it became unusable. On the appointed day, having exchanged our prisoners’ uniforms for civilian clothing, we downed some liquor to boost our courage - and to reinforce our story about getting drunk in the event of being captured. In the course of our escape preparations, I ran into a fellow townsman. As I passed by, I muttered: “If you hear the alarm tonight, that will tell you I’ve escaped.” During the afternoon, we slipped out of the camp. We entered the pit, and Feivele covered us with the iron plate and with soil, and sprinkled tobacco to prevent the SS tracker dogs from detecting our scent. We heard the camp sirens sounding the alarm: the search was on for missing prisoners. We heard the tracker dogs barking overhead. We held our breath, not so much as daring to blink an eyelid, so as not to be heard. Our situation was, however, unbearable. The pit was narrow, and its air vents had apparently been blocked; remaining there was out of the question. “I’m suffocating,” muttered the Pole, his feelings put into poignant words that infected the Russian and me. It took us only a short while to realize that we would not be able to remain in our hideout until the alert was called off. At about one that night, when silence surrounded us, we held a whispered consultation marked by indecision; foreseeing that we would not be able to hold out a single day in the pit, we resolved to leave that very night and continue our journey. Slowly and cautiously, taking great care to emit no sound, we removed the iron sheet from the pit where we were huddled. With bated breath, we crawled out on our bellies and began advancing toward open terrain. We managed to slip past the watch towers, but after making some headway, the sentries, possibly hearing something, opened fire. When we judged ourselves to be out of range, we clambered to our feet and began running. After running about 11 miles under the cover of darkness, we reached a bridge over the river Vistula. I learned subsequently that, upon discovering our escape, the camp’s security officials had promptly sent a telegram to the security services in Berlin. I found a duplicate of the original in the Auschwitz archives. Dated “Auschwitz, 30.6.44,” it offered particulars about our trio: 1. Paluch Mieczyslaw, born 14.1.1910 … Most recent address … Height 1.65 meters … brown hair presently cropped, speaks Polish, brown eyes. Back in the camp, we were confined to a cell in the political department, and our interrogation commenced. In particular, our interrogators demanded to know the whereabouts of the last of our trio. “Where is the third one?” We feigned innocence. “There were only the two of us. We got drunk and lost our way…” The interrogators of the political department, under the notorious killer Boger, gave us no reprieve for weeks on end. Our interrogator’s secretary, a Slovakian Jewess by the name of Katia, was of great help to us; indeed, she may have saved our lives. When the interrogator left the interrogation room briefly, she hastened to whisper: “Whatever happens, you must stick to your story. Let’s hope they don’t catch the Russian, and that he doesn’t tell a different version.” The Russian was not captured, and we did indeed stick to our story; accordingly, we were spared the death sentence and condemned instead to lifelong labor with the punitive squad. At evening roll call, we were seated in a special rack, in full view of all the camp inmates. Our sentence was read out - “for the offense of attempting to escape” - and our bare buttocks were subjected to 25 lashes from a fearsome leather whip. After that lashing, several weeks passed before I was able to sit down. I found myself once again in the punishment block - Birkenau’s Block 11 - this time as a dangerous criminal with a round red patch. In October 1944, the Russian front drew nearer to the death camps and the Germans decided to evacuate Auschwitz-Birkenau and move the inmates away from the eastern battlefront, to Buchenwald. The transport, totaling over 10,000 prisoners, was one of the largest ever to leave the camps. With so many prisoners being moved, those of us in the punitive squad contrived to mingle with the others, putting ourselves on equal footing by removing the red patches from our uniforms. On our way, we passed through various camps: Oranienburg, the site of the Heinkel aircraft factory; Sachsenhausen, where we met numerous Jews whose talents the Nazis exploited for forging documents, passports in particular; a new camp named Ohrdruf, near Gotha; and Grawinkel, where a mountain was being excavated to house the Fuehrer’s new headquarters. From an administrative standpoint, the camp was attached to Buchenwald. We were housed in subterranean structures designed as ammunition stores. In November or December 1944, after about two months in the new camp, and with the battlefront drawing near, the Germans again decided to evacuate us, back to Buchenwald this time. There appears to have been no trains available, and we - some ten thousand prisoners - were accordingly taken over 50 miles by foot. Stragglers were shot dead by the roadside. We marched for several days, sleeping in the open at night. Many reached Buchenwald at their last gasp. In Buchenwald, all prisoners mingled together. A prisoner’s status was denoted by his identifying patches, and since we had removed our Jewish insignia, the Germans were no longer able to distinguish Jews from Gentiles. On being re-registered, we presented ourselves as non-Jewish Poles, endeavoring to adopt names whose pronunciation or at least, initials, resembled those of our true names, so as to make them easier to memorize. “Your name?” the clerk asked me. There was no room in Buchenwald for all the prisoners. That appears to have been one reason for the German decision to evacuate this camp too. We were loaded on a train. The Jews were sent to Theresienstadt, while the Poles and those posing as Poles were consigned to the nearby camp at Leitmeritz, which was a kind of labor camp for the Flossenbürg concentration camp. In view of the situation and the rapidly growing chaos we observed in the camp, I approached two of my friends and suggested that we join the next transport leaving the camp in attempt to escape en rout. We did not know where any particular transport was headed, but we had no intention of reaching the final destination. We knew we were on what had formerly been Czechoslovak soil. Resolving to escape, we joined a transport which, in place of the customary freight wagons, was carried in passenger cars - an indication of Germany’s present predicament, which was marked by chaos and confusion. We were convinced this escape attempt would succeed. We were experienced escapees. Like me, my friends knew that should we be caught once more, the Germans would lose no time in executing us. But we also knew that we had slim chances of surviving the present trek. Nonetheless, an escape attempt was preferable to certain death. The transport set out. No one knew where it was headed. As for our trio - we were determined to seize upon the first opportunity to flee. At one of the stations, when our train halted alongside a coal train, we exchanged glances. The same thought ran through each of our heads: This is it! As one man, we leapt from our seats; vaulting to the coal train, we flung ourselves flat onto the coal heap. The Germans had not spotted us. The coal train arrived at the railroad station in the seventh district of Prague, the capital of Czechoslovakia. This station, located in the area known as Holishovitze, was at the time the site of coal stores. We arrived in the morning. Still wearing our prisoners’ uniforms, we stood behind one of the station buildings, amidst the heaps of coal, uncertain what to do next. Dawn broke, bringing a growing risk of discovery by some passerby. Suddenly, we spotted a boy and a girl, whom we took for high school students on their way to class. (We learned subsequently that the boy was headed for a pharmacy where he was employed as a messenger and apprentice pharmacist.) Taking our lives in our hands, we stepped out of our hiding place and stopped them. Addressing the boy with gestures and words of Polish and Russian - languages which bear a considerable resemblance to Czech - we conveyed our need for clothing. The boy replied in Czech, accompanied by gestures. Pointing to his watch, he said “Pockai”. ‘Czekaj’ in Polish means “wait”. We understood that he was advising us to wait for him. He hastened to return the way he had come.

The boy was Jindrich, only son of the midwife Jirina Sobotka and her husband Jindrich. Jirina was the sister of Vlasta Koushova, the secretary of Czech foreign minister Jan Masaryk. They were a family of Czech patriots connected with the anti-German underground. Jindrich returned home, where he took three suits from the closet, packed them in a small suitcase and walked out. Jindrich brought the clothing to our rail station hideout. While he served as lookout, keeping watch in all directions, we discarded our prisoners’ uniforms for the ill-fitting civilian clothes. Beckoning us to follow him, he led us by way of the alleys to his family’s modest home, a two-room apartment which also housed his grandmother. Mother Sobotka gave us one swift glance and hastened to put the kettle on the stove. Then she instructed us to undress and, drawing upon her midwifery skills, used a brush, soap, alcohol disinfectant, and hot water to scrub us clean of our accumulated concentration camp filth. Since we were circumcised, she must have guessed that we were Jews, but said nothing.

Although quite willing to conceal us and help us out with food and clothing, the Sobotkas immediately set about seeking a haven safer than their own apartment. Hrstka, a family friend and an officer in the prewar Czech army, owned a shop which sold artificial flowers. With times hard, the lack of raw materials and the absence of potential customers had led Hrstka to close down the shop; he now consented to hide us in his shop. Shortly after we exchanged the apartment for the storeroom, the Germans conducted a search of the Sobotka home, which was under constant surveillance. Fortunately, they did not demand explanations about the food prepared in the kitchen for delivery to us. We spent about three weeks in the flower shop. Sobotka family members and friends took turns bringing food to us in our hideout. In mid April, the Czech resistance took up arms, rising to attack and harass the Germans as they retreated from Prague. The Czechs were eager to drive the occupiers from their capital before they could reduce it to “scorched earth”. Hrstka, who had sheltered us in his artificial flower shop, was a senior officer in the underground; he took a brief break to come and tell us, with shining eyes: “My company is setting out to engage the Germans. Do you wish to join the liberation fighters?” Although still weak from the years of tribulation we had endured, we jumped at his invitation. We were issued arms and ammunition - whose weight virtually equaled ours - and given hasty training; our main duties were as guards securing the second line. On May 8, the Russians reached Prague. Our share in the drive to free the Czech capital earned us decorations and documents attesting to our having taken part in the city’s liberation. Hrstka escorted us to the population registry, where he saw to it that we were issued provisional documents classifying us as Czech citizens until the authorities got around to approving our naturalization.

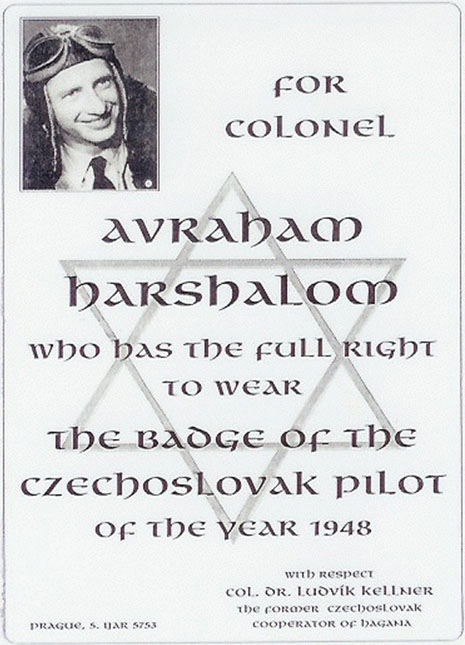

It was only after November 29, 1947, when the U.N. General Assembly resolved to partition Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, that I began to foster closer links with Palestine’s Jewish Yishuv as it embarked upon ints War of Independence. Emissaries of the Jewish militia, the ‘Hagana’ came to Czechoslovakia to recruit Jewish student volunteers. Volunteers were also sought for a pilots’ course organized by the Czech air force in an effort to aid the Hagana’s fledgling “air service” (which was to emerge as the I.D.F. air force after Israel’s official proclamation on May 15, 1948). I was among a group of 23 young Czechs who responded to the call, though my aim was not to make my home in Israel, but merely to help the nascent state ward off its enemies. This readiness to aid the Jewish Yishuv in its war for independence arose from the mood then prevalent in Czech political circles. The Zionist cause, which had achieved recognition through the U.N. partition resolution, enjoyed the sympathies of Prague’s democratic government. Consequently, the Czechs (certainly with the consent, if not active encouragement of the Soviet Union) concluded agreements with Hagana representatives, pledging a broad spectrum of aid, ranging from deliveries of weaponry (principally, planes and rifles), by way of bases for arms purchases, to the recruitment and professional training of volunteers from the various forces of the fledgling state. In his memoirs “They Took Off in the Darkness”, Benyamin Kagan (later to become an I.D.F. lieutenant colonel) recalled that on April 23, 1948, some three weeks prior to Israel’s official declaration of independence, 10 Messerschmidt fighters, with spare parts and ammunition, were purchased in Czechoslovakia. The deal included training in Czechoslovakia for pilots and mechanics; Czech experts were also sent to Israel to help reassemble the planes that had been dismantled for transportation. It was further concluded with the Czech government that the arms would be shipped in Dakota D.C. 3 transport planes, and C-46’s would carry the dismantled fighters. On May 20, an agreement was concluded in Prague for the purchase by Israel of 15 additional Messerschmidts; however, possessing no more planes of that type, the Czechs offered Spitfires formerly supplied to their “Free Czech” air force; these planes were familiar to Jewish pilots from Palestine who had served with Britain's R.A.F. during World War II, and to foreign volunteers.

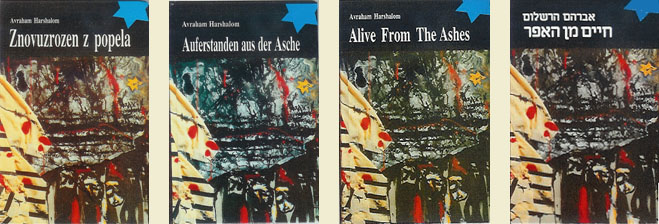

On completing our course in Czechoslovakia, we did not find it easy to reach Israel. I traversed part of the way overland to Italy and proceeded thereafter by ship. It was the end of March 1949 when I reached Israel. Although the fighting had ended, I continued to serve with the air force. However, I did not regard my military service as a profession. Along with an air force colleague, I planned my emergence into civilian life, all the while maintaining close links with the air force. Before I gave up my uniform, the air force granted me two personal services: an air force plastic surgeon removed the number the Nazis had tattooed on my arm (I have kept the scrap of skin in a drawer as a souvenir of eternal infamy); and, on February 20, 1951, the air force’s chief rabbi held a wedding ceremony for me and the wife of my choice, Rachel Rosenberg. When I founded my company in 1951, I named it “Ariel”, for the air force base in Jaffa. “Ariel”’s modest first steps were taken while I was still in uniform. After I established my business, I started flying again. First I bought a one-engine Piper Cherokee together with some friends, a few years later a Piper Twin Commanchee, and then a Piper Aztec - all second-hand. In the 80s I ordered a new Piper Aztec, which I fly until today. Several times I tried to visit Czechoslovakia after I went into business, but the gates were closed. In fact, for me it was even harder to gain entrance than for other Israelis, since on the visa application form my answer to the question if I had ever lived in Czechoslovakia was “yes”. The communist government didn’t like it. In 1987 I made a journey to my past, visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau, my home town of Pruzany, and Prague. During Gorbachov’s Perestoyka I finally obtained a visa. At Auschwitz I received original documents in which my name was mentioned, and I promised the director of the museum that I would record my memories for the museum. After my return, I decided to write the book “Alive from the Ashes”, instead of just collecting partial memories. Until now, two Hebrew editions of the book have been published and it has been translated into English, German and Czech.

After Czechoslovakia was freed from communism in the early 90s, diplomatic relations between Israel and Czechoslovakia were re-established. When the President of Czechoslovakia, Vaclav Havel, visited Israel, I was invited to a reception in his honor. A little while later I applied again for a permit to visit Czechoslovakia, and this time the visa was granted without any difficulties. The first time I traveled alone to see if I could track down everyone that I had known in Czechoslovakia at the time of and in the years immediately following World War II. I was able to find and renew my relationships with most of them. When I returned once again and visited with my eldest son and daughter (my younger son was in the army at the time) to show them the story of my life, I was welcomed as an official guest of the Ministry of Foreign Trade by a government car with a driver. We visited the shop in Prague where I had been hidden. The shop still stood where it had been before, but it was closed. Another get together that I participated in while in Czechoslovakia represented a different part of my life: my period of training as a pilot in the Czechoslovakian air force that aided the Israeli air force during the War of Independence. At this event my book, translated into Czech, was distributed to the Israelis and Czechoslovakians in attendance. Most of them had passed military courses in Czechoslovakia in 1948; the others were Czechoslovakian military instructors and official guests.

The gathering of pilots in Prague was organized by Dr. Ludvik Kellner, the historian who had worked in the headquarters of the Czechoslovakian military and had been the liaison between the Czechoslovakian army and the Hagana regarding the training of the pilots and the paratroopers that volunteered to help during the War of Independence. At this ceremony, we unveiled at the military museum in Prague, a plaque to commemorate the friendship between Czechoslovakia and Israel and the support that had been provided during Israel's War of Independence. A copy of the same plaque was placed in the "Altneushul" Synagogue near the old Jewish cemetery in Prague.

The second origins trip with my family and film crew was planned with my 80th birthday in mind. The premiere of the movie "Alive From the Ashes" was shown at my birthday celebration at "Beit Heil Ha'Avir" (The Air Force Center) in Herzliya. |

|

||||||